On Governance, State, and the Institutions of Justice

Thus far in these essays, I have argued from my metaphilosophy to my general philosophy of commensurablism, which is any philosophy that is neither dogmatic nor cynical, and neither transcendent nor relativist.

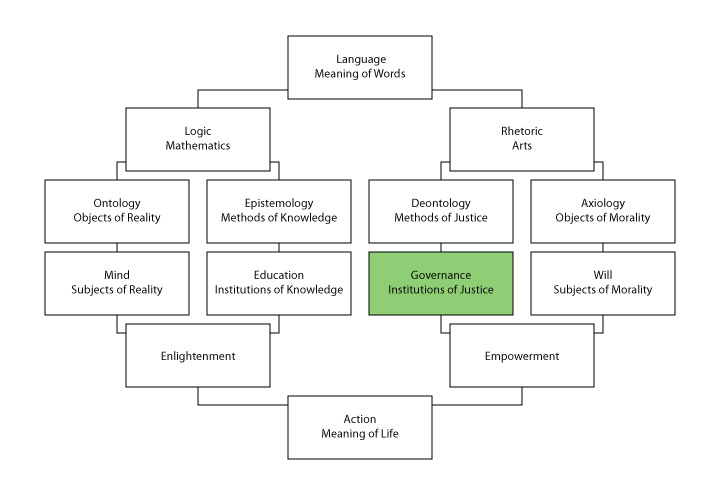

Then I explored the implications of commensurablism on the philosophy of language, including both logic and rhetoric; and its implications concerning reality and knowledge, including ontology, mind, epistemology, and education.

Then I began exploring its implications on the specific subtopics of philosophy concerning morality and justice, beginning with axiology, will, and deontology.

In this essay I will now conclude that series concerning morality and justice by exploring the implications of that liberal deontology on the philosophy of governance.

I will address political philosophy, or the philosophy of governance, as an analogue to the philosophy of education. Where the latter is concerned with the social institutions of knowledge, especially as they relate to the epistemic authorities called religions, philosophy of governance as I mean it here it is concerned with the social institutions of justice, especially as they relate to the deontic authorities called states.

As should already be clear from my previous essays on justice and especially against dogmatism, I am broadly against the validity of any supposed deontic authority, and so against the deontic legitimacy of any state, where that term is understood to mean some institute that claims such authority. (The traditional definition of a state, in political science and political philosophy, is an institute that claims a monopoly on the legitimate use of violence, which I take as equivalent to claiming such deontic authority, inasmuch as such a monopoly amounts to a claim that all and only their commands must be obeyed and that disobedience thereto justifies punishment, the application of violence). To recap the argument for that position:

- The task of philosophy is to find a way of discerning correct answers from incorrect answers to questions of any kind, whether about what is real or true or existent, or about what is moral or good or valuable.

- The position that there is always a question as to which opinion, and whether or to what extent any opinion, is correct, is to be called "criticism", and its negation "dogmatism".

- If we assume dogmatism rather than criticism, then in case our opinions do happen to be incorrect after all, we will never find out, because we never question them, and we will remain incorrect forever.

- Therefore to successfully do philosophy at all we must at least tacitly assume criticism, rejecting dogmatism.

This position against the validity of any supposed deontic authority, and so against the deontic legitimacy of any state, is generally called anarchism, specifically philosophical anarchism. But such philosophical anarchism does not mean that I am against all or necessarily any of the prescriptive claims issued forth by such institutions; only that I am against them being taken as authoritative simply for being issued by such institutions. And just because I am against any such institution being taken as deontically authoritative does not mean that I am against all social institutions seeking to promote justice.

On Legislation

I am very much in favor of a widespread, global collaborative process of many individuals sharing their insights into the nature of morality, checking each other's findings, and collating the resulting consensus together into the closest thing to an authoritative understanding of morality that it is possible to create, for the reference of others who have not undertaken such an exhaustive process themselves.

The proviso is simply that that resulting product should always be understood to be a work in progress, always open to question and revision – though it should in time become more and more hardened such that questions to which it does not already have answers become more and more difficult to find, and so large revisions to it become more and more difficult to make.

This is essentially analogous to the process of peer review already widely in use in contemporary academia for the purpose of building knowledge about reality. I am proposing here that a formally similar process, but grounded in the criteria for prescriptive judgement laid out in my earlier essay on value rather than the criteria for descriptive judgement laid out in my earlier essay on existence, can be used to collaboratively compile what amount to law books, rather than textbooks; still fallible, as our judgement cannot help but be, but procedurally narrowing in ever closer to a universal view of justice and morality.

As with the peer review process already laid out in my previous essay on education, this legislative process would also proceed in three broad phases. In the first phase, analogous to the creation of primary sources in a typical academic peer review process, detailed accounts are to be published, not of observations or sensations, but rather of appetites, as defined in my previous essays on value and on language. In short, people are to publish that under some specific circumstances someone experienced pain or hunger or some other such thing, detailed in such a way that others can later attempt to replicate those circumstances and see if they experience the same phenomena.

These primary sources can also share the conclusions their authors draw from their experiences – what actions or states of affairs they infer are good or bad on the basis of those experiences of things feeling good or bad – but the detailing of the experiences and the circumstances in which they were had, including the makeup of the people having the experiences (analogous to detailing of instruments used to make observations), is the most important element, so that other people can replicate those circumstances and control for differences between themselves to confirm that in such circumstances such people actually do have such experiences, reliably and repeatably.

Like the replicability of observations in typical academic peer review, this replicability of appetitive experiences is what grounds my proposed "poitical peer review" in universality, and provides a common ground against which to judge our ideas of what actions or states of affairs are good or bad, right or wrong.

In the second phase of the process, analogous to the compilation of secondary sources in typical academic peer review, groups of other people are to review and comment on the quality of that original research in media such as journals, republishing the original research that they find worthy in the process. Then in the third phase, still others are to gauge the consensus opinion held between those secondary sources on what can somewhat reliably, though of course alway still tentatively, be said about what is moral, and publish those conclusions in more accessible summary works, tertiary sources; essentially, law books.

These reference works are thus the closest things to deontically authoritative texts that are possible, the reasonable substitute for authoritative state law books traditionally taken as capable of defining what is just by fiat alone; though these tertiary sources are not to be taken so authoritatively, but understood as merely the best findings about morality that are as yet available, the strategies that have survived not only the hedonic testing of some individual researcher, but also the heavy criticism of everyone else participating in this endeavor throughout the world.

On Adjudication

Aside from that multi-tiered process of legislation just described to produce an alternative to traditional law books, an entirely different but valuable social role that state governance traditionally serves is that of adjudication. In other words, courts, or judges: powerful and just people who are well-versed in the "authoritative" texts – a state's law books in the traditional role, but the tertiary reference books in this anarchist version – to whom laypeople can come if they have individual questions about what is right or wrong to do, or to whom parties in a dispute about that can come for mediation and adjudication.

The answers given by such a person are not to be taken on their own personal authority, but on the "authority", such as it is, of the entire global process leading to the production of the reference works to which the judge refers for their answers. Such judges should be free to choose the reference works that they find best to use in this process, and individuals or disputing parties coming to them for answers or mediation should be free to choose judges that they find best to use for their purposes, including for the reason of their choice of reference works.

Furthermore, the reference works should not be taken by the judges as infallible, and in each case it should be possible in principle – though increasingly more difficult in practice over time – to successfully challenge the claims of the reference works, and in doing so force a revision to them. In this way the entire process remains technically non-authoritative, with lay people merely choosing to invest those who they judge to be more powerful and just than themselves with a transient semblance of authority to help them better figure out what to do for themselves, or to settle arguments that they cannot settle between themselves. (How to resolve cases where different parties to the same dispute appeal to different judges for mediation is addressed later in this essay.)

On Correction

Still aside from that reactive judicial role, I hold that it is also important to have, as most societies already do, more proactive correctional roles, like public patrols; but also, analogous to teachers in the academic sphere, something like life coaches or a business's in-house lawyers.

The role of such a coach, as distinct from a judge, would be to actively guide their clients to intend to do things that are probably good, according to those same collaborative works of legislation referred to by judges, rather than merely to be there to answer questions and resolve disputes as they come up. The coach provides the clients with answers to questions they hadn't even thought to ask yet, and in doing so hopefully helps to prevent disputes from coming up between them in the first place, advising their clients on how to avoid doing things that are likely to get someone else to bring their judges down to bear on them.

To keep this coach role from becoming too authoritative, though – to keep it from becoming mere command of one person by another – I think, like many political philosophers of recent centuries, that it's important to maintain a separation of the governmental roles of executive (of which the coach is one form), judiciary, and legislature; analogous to the separation of teaching, testing, and research outlined in my previous essay on education. A coach should not be advising about laws that they wrote themselves, nor judging their own clients on their compliance with them; and neither should a judge be the author of the laws against which people are judged.

Rather, the laws should be a result of the global legislative process detailed earlier in this essay; accordance with it should be judged by someone in the judicial role described above, someone well-versed in those laws; and the coaching of people to live in accordance with those laws should be done by a separate party, coaching to the same laws as the person who will later judge them, but independent of that judgement.

In this way the coach cannot, upon passing their own judgement, simply rule in favor of those doing things the coach is in favor of and against those doing contrary, but must correctly guide their clients to live in accordance with an independent system of laws that someone else, also independent of the authorship of those laws, will judge them against; and in this way no person involved in governance can exercise unbridled deontic authority over anyone.

Another more familiar role, executive in nature like that of a coach but even more proactive still, is that of public patrols, who rather than guiding only those clients who come to them seeking personal guidance, that being still a reactive process in a way, instead look out over society and step up to act against wrongs where they see them. This begins to veer dangerously close to the public patrol asserting their own deontic authority over others, and to make sure that it does not come to that, this process must wind up turning to an independent, mutually agreed-upon judge figure to settle the resulting argument, by reference to still-more-independent law books that are the product of the global legislative project detailed earlier in this essay.

But I think that it is important to have such public patrols going out and standing up to wrongs done in society, making sure someone stands up to the wrongdoers and they don't just go unchallenged, even as dangerously close to authoritarianism as that might veer, because anarchism is by its very anti-authoritarian nature paradoxically vulnerable to small pockets of deontic authority arising out of the power vacuum, and if that instability goes completely unchecked, it can easily threaten to destroy the anarchic society entirely and collapse it into a new, deontically authoritarian regime; a state in effect, even if not in name.

On Stateless Governance

In the absence of good governance of the general populace, all manner of little proto-states may still spring up, in the form of gangs, warlords, and other strongmen asserting their will over anyone else who is too weak to resist them; and left unchecked, these gangs can easily become actual full-blown states, their personal abuses of power becoming widespread, socially-acceptable injustice, that can appropriate the veneer of deontic authority and force their injustice on others under the guise of justice. Checking the spread of such injustice by challenging it in society is the role of public patrols.

The need for that role would be lessened if more people would actively seek out governance from coaches or judges as I have described them above, but not everyone will seek out their own governance and so some people will continue to spread injustice – and even those who do seek out their own governance may still accidentally spread injustice – and in that event, there need to be public patrols to stand against that. But that then veers awfully close to proposing effectively another state to counter the growth of others.

There is an apparent paradox here, in that a society abhors a power vacuum and so the only way to keep states, institutions claiming deontic authority, at bay, is in effect to have one strong enough to do so already in place. That is essentially the justification Thomas Hobbes gives for supporting absolute monarchy in his Leviathan. But I think there is still hope for liberty, in that not all states are equally authoritarian: some have their laws handed down through strict decisions and hierarchies, while others more democratically decide what they as a society demand from their citizens. I think that the best that we can hope for is a "state", or rather a (stateless) political or governmental system, that enshrines the principles of anarchism, and is structured in a way consistent with those principles.

Such a system of anarchic governance is somewhat analogous to how, in my essay on the will, I held that "will" in one sense is present in all causation, and neither something beyond causality that imposes itself upon causal chains, nor something that spontaneously arises from certain configurations of causes and effects, but nevertheless something that can be refined by certain configurations of them; and proper will per se requires such configurations and doesn't exist in just any random causal chain, but nevertheless still consists of nothing above or beyond simply refined arrangements of the same fundamental "will" omnipresent in all causation.

So too, here I hold deontic "authority" to be present in all people, and neither something beyond people that imposes itself upon people, nor something that spontaneously arises from certain configurations of people, but nevertheless something that can be refined by certain configurations of people; and proper governance requires such configurations of people and doesn't exist in just any random amalgam of people, but nevertheless still consists of nothing above or beyond simply refined arrangements of the same fundamental "authority" omnipresent in all people.

The ideal form of such a system of governance would, I think, see the judicial role described above as the central figure, to whom laypeople come with disputes to be resolved. Those judges then turn, on the one hand, to the authors of the "law books" as described above to make their rulings about what is or isn't just, who in turn turn to authors of legislative secondary sources, who in turn turn to the authors of legislative primary sources, as described above; while on the other hand the judges turn to coaches and to public patrols to enforce their rulings. When there is a dispute between two people who cannot mutually agree on one judge to resolve their conflict, they can each call upon their own separate judges to step in and resolve the argument between themselves.

If need be, if even the judges cannot reach an agreement between themselves, they can turn to yet another mutually agreed upon judge to resolve the resulting conflict between them, or else escalate further on, until at some point the argument is escalated to some parties who can work out an agreement on the matter between them, or to some mutually agreed upon arbiter who can decide the matter, and in either case then pass the decision back down the chain; unless, in the worse case scenario, an irreconcilable rift in society is discovered, in which case there is no perfect solution regardless of the system of governance we have in place.

On Pragmatic Compromise

Despite the utopian ideals detailed above, I recognize also that we should not let perfect be the enemy of good, and that the choice should not be between either a perfectly functioning anarchic governmental system or no governmental system at all, leaving in the latter case a power vacuum for the worse kinds of states to spring up unopposed. So it seems reasonable to me that there be in place a slightly-less-ideal, less anarchic, but for the same reason more stable system of governance in place already in case the ideal one should fail; say a social democracy, with the power to enact popularly supported laws and to socially redistribute capital.

It should, wherever possible, allow the ideal anarchic solution to function and stay out of its way, and only step in to ameliorate the gravest failures that would otherwise result in a collapse to something even worse than a democratic state. It can, for instance, resolve otherwise irreconcilable conflicts between the highest levels of the anarchic governmental organizations, and levy progressive taxes to fund a universal stipend to ensure that everyone can afford to subscribe to those organizations.

It may in turn be prudent to have more than just this one tier of such failsafe in place, to ensure that wherever a better system of governance fails, it fails only to the next-best alternative, rather than failing immediately to the worst alternative; say a monarchy elected through direct democratic vote, empowered only to defend the social democracy from outside threats and prevent any inside forces from taking it over from within.

I think that this kind of evolution from state capitalism toward anarcho-socialism is itself a natural progression of rational governments looking to preserve themselves.

Authoritarianism and hierarchy may form the default form of state, given the origins of states from imbalances of power, but such a state will survive longer against the threat of revolution if it asks its subjects what they want of it, and gives them a cut of its takings, naturally inclining such authoritarian, hierarchical states to evolve a layer of social democracy as a means of effectively buying the loyalty of its subjects, or else eventually fall to popular revolution. Such a social democracy can then most easily appease the most people if it simply lets them make their own lifestyle choices instead of telling them how to live, and lets them provide each other with services instead of trying to do so itself, adding a layer of anarchy.

Thus, the lazy selfish authority, acting in its own self-interest, naturally devolves power toward a social democracy; and a lazy selfish social democracy, acting in its own self-interest, naturally devolves power toward more anarchic ideals. (This progression is not unlike Karl Marx's historical expectations that feudalism and capitalism would evolve through a phase of state socialism toward an anarchic state of communism).

I don't expect that this process would naturally result in true anarchy on its own, but the trending of better states toward anarchy demonstrates an important principle: anarchy is not the opposite of governance, but the perfection of it, what a government that does more good things that governments should do and fewer bad things that governments shouldn't do tends toward.

A society may thus find itself over time sliding up and down the scale between the worst authoritarian rule and the best anarchy, depending on how well its participants manage to operate within the different possible governmental systems along that scale. Because in the end, it is inherently impossible to force a people to be free. How good of a governmental system a society will support ultimately depends entirely on how much the people of that society genuinely value justice, because that governmental system is made of people, and it is ultimately their collective pursuit of justice that determines how well-governed their society can be.

How exactly to help contribute toward getting enough people to pursue justice, morality, and goodness more generally, is the topic of the next essay.

Continue to the next essay, On Empowerment, Courage, and Serenity.

On Socialism

Maintaining a generally level balance of actual power in practice (not just legal power on paper) between all the members of society is of utmost importance to making sure that such an anarchic government can continue to function properly, because if some people have such practical power over others, they have the ability to coerce those others into doing as they say, and so begin to wield effective deontic authority which can then easily grow into a proper state. (Such as if, for example, some people have the means to hire judges who employ more powerful enforcers than others, and so judges in disagreement have no need to appeal upward because one can just unilaterally enforce their decision on the other and their clients, effectively asserting deontic authority).

Because of this interdependence between liberty and equality, anarchic governance requires a socialist economy. This does not mean a command economy, where everything is owned by the government who then directs everyone how to use it; that would obviously be a state, and so not anarchic. "Socialism" means only that the populace cannot be divided into those who own the things that everyone needs to work and survive, called capital, and those who labor upon that capital at the direction of those owners; instead, people should own the things that they use, like their homes and workplaces, and neither own the things that other people need to use, nor need to use things that other people own.

In contrast, such a division of ownership and labor is the proper meaning of the term "capitalism"; not merely a free market, which in turn is just the opposite of a command economy. Anarchism definitionally requires a free market, but in practice it cannot survive alongside capitalism, as the capital owners would merely be the new state. Similarly, socialism cannot in practice survive alongside a state, as whoever leads the state, that controls all the capital, in effect become the new capital owners.

Just as it was not until mysterianism was done away with, and truths were actively and eagerly shared (proselytically), that there was any groundwork laid for doing physical sciences, that in turn provided a plausible alternative to religions, so too it won't be until capitalism is done away with, and goods are being actively and eagerly shared (socialistically), that there will be any groundwork laid for doing ethical sciences, that in turn can provide a plausible alternative to states.

I think that the libertarian deontic principles I have laid out in my earlier essay on justice, if followed, would result in an economy trending toward a socialist distribution of capital over time, without the need for state intervention to redistribute it, or the the abolishment of all private property to allow people to freely seize it. The principal difference between my principles and other libertarian principles that either abolish private property ("left-libertarianism") or else allow capitalism ("right-libertarianism") is the limit on the power to contract, especially as it regards contracts of rent and interest (collectively "usury", a fee for use).

Right-libertarian theory generally expects that those who possess capital beyond their own needs will sell it to pay for labor (so as to give themselves leisure) from those who possess less capital than they need, who can in turn use that pay to buy the capital they need, and in this way the free trade between owners and laborers will, they suppose, naturally dissolve the class divide and tend to equalize the distribution of ownership and labor. This is commonly referred to as "trickle-down economics".

This observably does not happen in practice, and the reason for that is, I think, the existence of usury, whereby those who own more than they need can instead lend it to those who need more than they own, who then pay for that with the money they are paid for their labor by such owners, but then have to give back the lent property, so that what the owner class pays the worker class generally comes right back to them, more reliably the greater the divide between the classes is.

If instead contracts of usury were powerless, and so such arrangements legally unprotected, those who own more than they need would have no way to benefit from it other than by selling it, and as nobody else who has more than they need would be buying it as an investment vehicle to lend out, they would only be able to sell it to those who need more than they have, on terms that such buyers are able to afford. If they did not agree to sell on such terms, those in the owner class would take a complete loss on their investments in their excess property, so whatever those affordable terms are, it is in the owners' best interest to sell on them rather than not sell at all, and so in the absence of contracts of usury, the ideal free-trade redistribution of property that right-libertarian theory expects would actually happen.

Despite the interdependency of liberty and equality described above, many people try to advocate for anarcho-capitalism or for state socialism, treating liberty and equality as independent, and creating a two-dimensional spectrum of political systems.

In one corner of this spectrum are those who advocate for an unlimited state and unlimited capitalism, state capitalists, who include both medieval feudalists (where those who owned land, the productive capital of the time, were the same nobility who constituted the government) and fascists in the sense originally coined by Mussolini (who said it might better have been called "corporativism", consisting as it did of a collusion between big businesses and big government).

Most modern political positions advocate for a more limited state, but still a state, and differ largely on whether capitalism in that limited state should be unlimited (so-called "conservatives" on the right of this spectrum), those who think it should be allowed but limited (so-called "moderates" in the "center" of this small part of the spectrum), and those who think that it should be minimized if not entirely eliminated (so-called "progressives" on the left of this small part of the spectrum). Within the range of various degrees of limited capitalism, there are also those who advocate for a greater state, authoritarians erroneously reckoned as being on the "left" of (this small part of) the spectrum, and those who advocate for a lesser state, libertarians erroneously reckoned as being on the "right" of (this small part of) the spectrum.

In the upper-left corner of that lower-right quadrant where all these positions fall, right on the edge of eliminating the state but not all government and capitalism but not all private property, is my position. In the further outer reaches of the political spectrum, there are those who advocate the abolishment of not only capitalism but of private property, including many of both state socialists and some anarcho-socialists; and those those who advocate eliminating not only the state but all government, including both anarcho-capitalists and some anarcho-socialists. Beyond all them still are a few who advocate for not even allowing self-defense or personal possessions, like some anarcho-pacifists, in the far corner most opposite the state capitalists.

I advocate for a gradual political evolution away from state capitalism along the diagonal toward my centrist position, neither veering too far above it nor to the left of it, even though I want upward and leftward motion, because to imbalance the power of the state against the power of capitalism threatens to veer into state socialism or anarcho-capitalism, both of which, lacking either liberty or equality, I see as completely untenable in the other aspect, as described above, and so tantamount to state capitalism again.

Because of the interdependence of liberty and equality described above, positions that veer too far into either state socialism or anarcho-capitalism tend to begin adopting the worst aspects of the other, both of them veering therefore toward state capitalism. This has the effect of bending the diagonal axis between them into a horseshoe shape in practice, with positions too far off the center of that axis tending toward the same worst-of-both conclusions, albeit from opposite directions.

You will note my many qualms about the usage of some terms like "conservative", "moderate", "progressive", "centrist", "left", and "right". I use them above in their more common usage to identify common positions on the spectrum, but I hold that that usage is technically incorrect. These terms originate from the French Revolution, during which supporters of the feudalist status quo of the time sat on the right of their parliament, while those who advocated a change to greater liberty and equality sat on the left. I hold that the proper referents of "left" and "right" are thus the directions away from and toward state capitalism, which forms a diagonal on this spectrum.

The emphasis first and foremost on liberty lead many to treat "left" and "liberal" as synonymous. But because the world powers of the Cold War were (at least nominally) libertarian capitalists of the First World and authoritarian socialists of the Second World, that perpendicular diagonal axis became the new common frame of reference for "left" and "right", leading some to even more generally associate "left" with authoritarianism and "right" with libertarianism. My qualms about what are commonly called "centrists" being called that is that they are only central within that limited quadrant of the spectrum, ignoring how much further away from statism and capitalism it is possible to advocate.

And my qualms about the terms "conservative", "moderate", and "progressive" are that those strictly speaking do not name where on the political spectrum one's ideal political system would fall, but how one approaches change toward their goal, wherever on the spectrum it should be. I hold that the proper referent of "conservative" is someone who is cautious about change, if not completely opposed to it; since the historical trend of change has been away from authority and hierarchy toward liberty and equality, the word has understandable connotations of authority and hierarchy, but does not strictly mean supporters thereof.

Conversely I hold that the proper referent of "progressive" is someone who pushes for some change, if not complete change; since the historical trend has been as above, the word has understandable connotations of liberty and equality, but does not strictly mean supporters thereof. And I hold that the proper referent of "moderate" is someone who is both conservative and progressive, pushing for some change, but cautious change; those progressives who are not moderate, pushing for complete change, are properly called "radicals", and those conservatives who are not moderate, completely opposing all change, are properly called "reactionaries".

I consider myself not only a true centrist on the full spectrum described above, but also a moderate in this sense of conservatively progressive, neither radical nor reactionary. I do not view either change or stasis as inherently superior to the other, for both creation and destruction are kinds of change, and both preservation and suppression are forms of stasis, suppression negating creation just as preservation negates destruction. And it's not even inherently better to create and preserve than to suppress and destroy, for worse things can be created or preserved, in the process destroying and suppressing better things, in which case it would be better to suppress or destroy those worse things so as to preserve and create better ones.

I support either change or stasis as they foster better results, neither unilaterally over the other. To that end, I generally advocate that things should get better as quickly as possibly for the people at the bottom, the worst-off; while getting no worse for the people in the middle, the average, though if conditions can be approved across the board, they should of course benefit as well. But if the improvements must come at anyone's expense, it consequently must be only that of the people at the top, the most well-to-do.

As should hopefully be evident by now, my entire politics is about balancing powers against each other and then diminishing them. (That is precisely why liberty requires equality: inequality is an imbalance of power, and imbalances of power create increases of power.) My ideal stateless government hinges on balancing the powers people have to harm each other, and then diminishing the harm they do to each other. My incremental approach to achieving that hinges on balancing the power of the state against the power of capital and then diminishing both of them. My moderate approach to pushing that agenda hinges on balancing the threat of radicals against the reactionary status quo.

On any of those fronts, whichever side is the weakest in a given context is the one I tentatively support in that context, but only to the extent of balancing it against the other power and then diminishing both. Radical libertarian socialists are useful to widen the Overton window (the popular perception of the range of political options) against the state capitalist status quo, but I don’t actually want them to win a violent revolution and drastically change everything overnight. State-socialist policies are a useful interim hedge against unregulated capitalism, but I don’t actually want that as the end-goal of political evolution. Libertarian capitalists are even useful allies against unchecked abuses of state power, but I don’t actually want their vision to win out either.